Think Before You Ban

How to Level Up Your Cost-Benefit Analysis

Even if some product or activity is deemed a net harm to society, it doesn’t automatically follow that it should be against the law. Putting aside the intangible cost to personal freedom, enforcing bans always involves doing or threatening to do things that most people agree are wrong– namely, robbery (fines), kidnapping (arrest and imprisonment) and killing (lethal force during attempted arrests), all funded by theft (taxation). Those costs should be factored in when considering whether or not to ban something.

This assertion seems like common sense to me, but I rarely see people take the intermediate steps between deciding that something is bad and deciding that it should be banned. From watching or participating in hundreds of debates about what should be illegal, I’ve identified several levels of analysis that people tend to operate on. I believe that everyone should require themselves to reach the deepest level before endorsing any kind of ban. In this post, I’m going to describe each level and give examples of policies that resulted from that type of thinking.

Level 1: I don’t like the thing, so it should be banned.

The most shallow possible level of cost-benefit analysis involves simply assessing how you ‘feel’ about something. If you like it, it’s probably a human right. If you don’t, it should be illegal. Few people will admit that this is as deep as their thinking is going, but there are ways to tell. If someone’s response to reasonable counterarguments is to try to change the topic, reply with nonsensical jargon, or call you names, they probably haven’t thought about the topic very much but just don’t want to admit it. Thankfully, few people in decision-making positions get stuck at this level; it’s relatively easy to google a few talking points so you don’t look like a total idiot when someone on the other side of the issue challenges you.

Example: catcalling. There are several countries where catcalling is a crime punishable by fines, community service, and even house arrest. Obviously, catcalling is childish and rude and makes most women feel uncomfortable, but it’s hard to point to any real, physical consequences from it. Spain’s ban defines catcalling as “[c]omments, propositions or behavior of a sexual nature that cause a situation of humiliation, hostility or intimidation.” Verbal intimidation and threats were already illegal under other Spanish laws, so it’s fair to say that the ban on catcalling is essentially a ban on otherwise harmless comments that women find rude or demeaning.

Source: Mirror

To state the obvious, I don’t approve of catcalling, but I also think making it a crime is excessive. Proponents of this ban typically say that women’s negative feelings towards catcalling are enough to justify outlawing it, or that catcalling leads to other more serious crimes like sexual assault. Given that sexual assault was also already illegal, it’s pretty clear that this ban was only passed to quell the emotional outrage of certain vocal activist groups. Opposition to the ban was usually met with hysterics rather than reasoned arguments, further evidencing the law’s largely emotional basis.

A few years ago, I got into an argument about this topic in which I opposed this ban, and my opponent’s immediate response was “well, have you ever been catcalled?” They were saying, in other words, “it’s true that an objective outside observer can’t find any serious negative consequences from catcalling, but experiencing it causes an internal subjective experience that doesn’t feel good and makes me want to punish those who do it.” Their argument did not get much further than this. Call me heartless, but I don’t think this qualifies as something that needs to be systematically punished by the state.

Level 2: The thing has negative consequences sometimes, so it should be banned.

People who love to ban things tend to be more sensitive to costs than benefits, so many of them never consider the benefits of certain things at all. Fortunately, I’ve found that it’s easy to push people from this level to the next. If someone says ‘factory farming is horrible because it kills animals, so we should end factory farming’, you can respond with ‘yes, but it also feeds billions of people’, after which one of two things typically happens: either they will say that the benefit you named is smaller than the cost they named, in which case they’ve moved to a deeper level of analysis, or they’ll get mad at you, in which case they were probably operating at level 1 all along.

Example: emitting lots of carbon dioxide. The ‘net-zero’ craze, where many companies, cities, states, or even countries are pledging to sequester as much CO2 as they emit, is largely a result of the delusion that anthropogenic CO2 is only bad, so we should emit as little of it as possible. I’ve even seen some proposals for ‘absolute zero’, which amount to little less than civilizational suicide. This craze has resulted in mountains of environmental regulations that either limit or criminalize CO2 emissions.

Most of our CO2-emitting activities are beneficial for humanity and well worth the environmental cost, but even if we only look at the emission itself, we find both positive and negative consequences. As I wrote in my overly-long piece on livestock emissions:

Many environmentalists tend to view global warming as an absolute, pure evil, despite how complicated of a phenomenon it is. For example, they often contend that it will simultaneously increase rainfall in places that are already too wet and increase drought in places that are already too dry, as if Satan himself has made sure that climate change does not accidentally benefit us in some way. This view is inaccurate, and frankly childish. Global warming, and even anthropogenic [greenhouse gas] emissions, have myriad effects, some of which are bad and some of which are good.

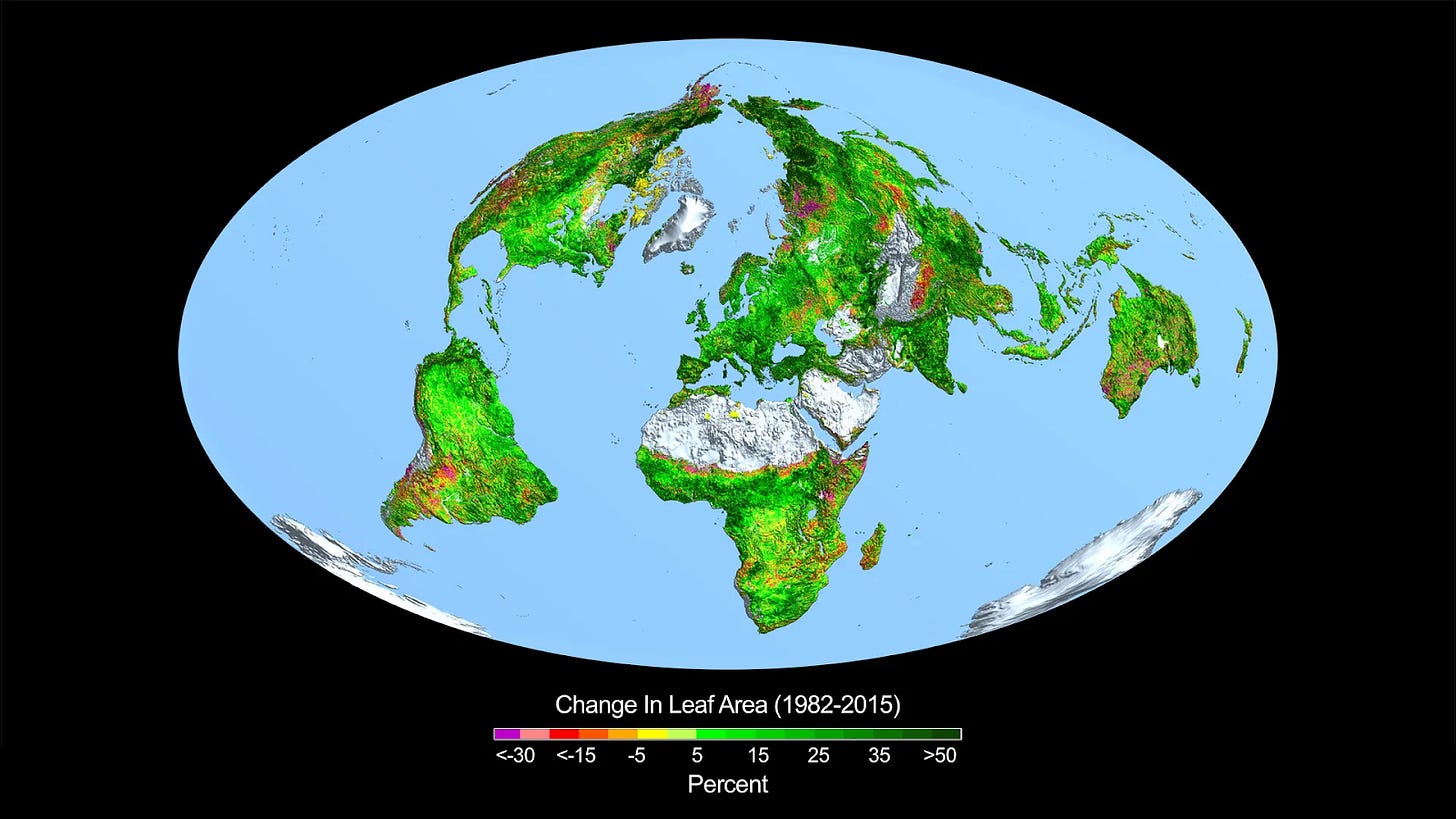

A very striking and well-established positive effect of increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is the CO2 fertilization effect, or ‘global greening’. Satellite data from NASA confirms that, over the last few decades, the Earth has added the area equivalent of one entire Amazon Rainforest in vegetation. Globally, the amount of green land area increased by around 5% from 2000 to 2020, with models estimating that 70% of this effect is due to the increase in carbon dioxide fertilization. In other words, our devilish, planet-destroying CO2 emissions are actually helping to terraform the planet for plant life.

How often are such positives considered– or even mentioned– when people debate regulating CO2 emissions? Hardly ever.

Source: NASA

Level 3: The thing has positives and negatives, but the negatives emotionally resonate with me and the positives don’t, so it should be banned.

This seems to be the most common level at which people get stuck (as an aside, I think participation in these levels is probably either normally distributed or left-skewed). Most people think far more emotionally than they are willing to admit. Couple this with the public’s oversensitivity to costs and you’ve got a recipe for heavily biased cost-benefit analysis where things that are scary, sad, or vivid get weighted more heavily.

It’s quite hard to move people from this level to the next, partly because it usually involves some tough talk: ‘yes, I know that this terrible tragedy seems like the only thing that matters, but if you were thinking rationally you’d feel differently’. Try that line on a hundred people and you’ll get at least 90 of them freaking out at you.

Very often, people who try to take the emotion out of cost-benefit analysis get accused of ignoring ‘nuances’, by which the accusers usually mean ‘unmeasurable complexities that have equally unmeasurable effects’. I’ve also been told that, by using statistics in my arguments, I’m ignoring ‘the human element’, which I gather mostly means ‘people’s feelings’. I’m not an emotionless robot, but I do think it’s reasonable for policymakers to ignore people’s feelings when making decisions, since feelings tend to lead us very far astray to decisions that cause large amounts of harm.

Example: Civilian gun ownership. The US has piles and piles of regulations restricting civilian ownership of firearms, and few make logical sense. Why are suppressors impossible to get without petitioning the ATF for approval and paying them an extortion fee? Because people watch movies and think suppressors are only useful for assassinations. Why are AR-15s banned in Washington when handguns are responsible for so many more deaths? Because ARs look scarier. I can’t prove it, but my gut tells me that most gun control laws are in place because the majority of people allow emotion to dictate how they feel about guns. One of the most restrictive gun control bills in this country was passed as a result of one high-profile assassination attempt on one very famous man, afterall.

Bill Clinton signs the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, mandating federal background checks on all firearm sales by licensed dealers.

Source: William J. Clinton Library

The fact that mass shootings and school shootings overwhelmingly dictate the tone of the American gun control debate despite accounting for a tiny fraction of all homicides further evidences the fact that vivid, tragic, and shocking events are more important to most people than statistical reality. Even if you can present someone with reliable data showing that most gun deaths are suicides and probably have nothing to do with the availability of firearms, or that defensive uses of firearms probably outnumber gun deaths several times over, or that gun control simply doesn’t reduce homicides, it’s all for nothing if they can’t weigh up costs and benefits correctly. If someone allows the tragedies they see on the news to guide their policy positions on guns, they are going to believe that AR-15s are high-powered assault weapons and they are going to say that no civilian should have them.

Gun control is the topic where it feels like people have the most trouble calming down and thinking rationally about how to minimize the loss of innocent life, for understandable reasons. Mass school shootings are horrific and difficult to process, and I wouldn’t berate anyone for struggling to quell their emotions when talking about them. However, I also wouldn’t have the parents of school shooting victims decide what our gun control laws should be, any more than I would want a panel stacked with the children of 9/11 victims to decide how much of our GDP should go to counter-terrorism efforts.

When courts select jurors, they try to avoid selecting people with some intense personal animus regarding the crime at hand because emotions can lead us astray. Even after such screening, juries still find it hard to be objective when it comes to guns, as evidenced by the fact that juries will be harsher on people who use weapons that are too scary-looking, too flashy, or too effective.

When it comes to topics that feature many emotionally resonant events, be it guns, terrorism, or immigration, always ask whether you are assigning too much weight to those outlier events and not enough to the things that characterize the vast majority of reality.

Level 4: The thing has positives and negatives, but the negatives outweigh the positives so it should be banned.

Most people seem to view this as the final and correct level when assessing whether something should be against the law. It seems reasonable enough to say ‘if X has more costs than benefits, X shouldn’t be allowed’, but this neglects to weigh up the costs of the ban itself, as my introduction hints.

Example: Recreational hard drugs. While most of the country seems to support fully decriminalizing recreational marijuana, far fewer people endorse the decriminalization of harder drugs. This is probably because marijuana has fewer downsides than harder drugs, and because many functional, normal people derive long run positives from using it. In contrast, it is extremely difficult to make the case that recreational heroin, meth, or fentanyl have long run positives at all, let alone ones that outweigh their obvious negatives. So, is personal freedom the only compelling case for decriminalization? Not necessarily.

When someone says 'the recreational use or sale of heroin should be illegal, and the punishment should be jail time’, they are not just saying ‘people shouldn’t do recreational heroin’. They are saying that anyone who tries to do recreational heroin or sells it to a willing customer should be taken, against their will, to a place where they are much more likely to experience violence, including sexual assault, and be kept there for a long time. They are saying that there should be a permanent demerit on their record that will make it harder for them to find jobs in the future, that they should be denied their rights to own firearms, and that they should be punished even more severely if they reoffend. For a nonviolent victimless crime, this seems excessive. In fact, it seems like a reliable way to turn harmless druggies into violent crooks.

It gets worse, however. Not only do drug prohibitionists endorse subjecting nonviolent people to violence and economic hardship, but they also want to make everyone else pay for it. Police, courts, and most prisons are ‘publically funded’, which is a euphemism for ‘funded with stolen money’. It would be one thing for prohibitionists to voluntarily donate some of their own money to an organization of thugs who promised to assault and kidnap peaceful drug users wherever they find them. Forcing everyone else in society to do it whether they agree with the ban or not is much less defensible.

Level 5: The thing has positives and negatives, but the negatives outweigh the positives by so much that I will endorse confiscating money from some people to hire other people to rob, kidnap, or kill anyone who does the thing.

If I had to guess why so few people reach this level, I would say that they aren’t thinking enough about what a ban really is. The way some people talk, it almost seems like they think making something illegal means magically removing it from existence. Reframing the punishments– e.g., saying ‘robbery’ instead of ‘fines’ and ‘kidnapping’ instead of ‘arrests’ – makes bans seem much less appealing to reasonable people. A normal person can much more easily say with a straight face that ‘people shouldn’t be allowed to watch porn’ than they can say ‘if anyone tries to watch porn they should be robbed, and if they won’t allow themselves to be robbed they should be kidnapped for several months or years, and if they won’t allow themselves to be kidnapped they should be killed. Also, I’m making you pay for all that’. That said, there are some things that are so unambiguously bad that they may warrant such punishments.

Example: Homicide. Obviously, people non-defensively killing each other is extremely bad, but even this ban is not without its downsides. Bryan Caplan recently posted a great piece pointing out that, for many laws, their potential downside is not that the laws will be enforced but that their targets will be incorrectly identified. In the case of laws against homicide, one risk is that a defensive killing will be incorrectly identified as a murder. Remember a few years ago when half of the country wanted an 18-year-old to be imprisoned or executed for committing three clear-cut and well-documented acts of desperate self-defense? Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed in the end, but the Rittenhouse trial serves as a reminder that an irrational public will often try to weaponize sensible laws for insensible ends.

Kyle Rittenhouse being attacked by rioters in Kenosha.

Source: NBC Chicago

There are also rare cases where we don’t want the laws against homicide to be enforced “correctly”. In 1984, Gary Plauché publicly shot and killed Jeffery Doucet, the man who kidnapped and molested his son, while Doucet was in police custody. This was obviously not self-defense, but most people would agree that this particular act of vigilante justice should be handled differently than a typical homicide. Despite the fact that the shooting was clearly premeditated, and despite Plauché clearly not feeling any remorse, the court reasonably concluded that he was not a threat to anyone else and that incarceration would serve no purpose. Plauché’s sentence was suspended and he got off with 5 years probation.

On paper, Gary murdered someone, but as he famously put it, “you'd do it too”. In this case, the court essentially defied the ban on homicide and delivered a ruling that was more in line with the common moral conviction that the parents of molestation victims should be allowed to take vengeance on pedophiles who harm their children.

Gary Plauché (left) moments before shooting and killing his son’s rapist.

Source: Springfield News Leader

The vast majority of killings that are prosecuted as homicide probably don’t fall into either of these categories, however. On the net, punishing killers with violence is appropriate. Maybe I’ve been reading too much anarchist literature, but I still hesitate to say that this price needs to be exacted by a publicly funded organization. However, the majority of people would probably voluntarily fund an organization that effectively policed homicide, so in theory this ban could be enforced through moral means. In general, it would lessen the moral cost of publicly funded policing if we only outlawed things that most normal people think should be punished with violence.

To recap, the title of this post is also its conclusion: think before you ban. If you find yourself wanting to ban something, you should ask yourself this question: do I want the government to steal money from other people and use it to fund systematic violence against those who do that thing? If your answer is yes, by all means, cast your vote. However, I would guess that people who start employing this standard would find themselves endorsing far fewer prohibitive laws.

While I’m sure I haven’t changed many minds about what should and shouldn’t be illegal, hopefully I’ve slightly raised the threshold which my readers use to determine whether something should be outlawed. At the time of writing, my sister and I are having a back-and-forth about whether certain artificial dyes should be banned from American food production. She and I both agree that these dyes are terrible poisons that have no business being in human food, but my threshold for endorsing a ban has not been reached yet; I am hesitant to give the government even more power over food production, and I see other, cheaper ways to get people to stop ingesting poison. In this case, weighing up the extra cost of the ban makes the difference between endorsing it and not. If everyone thought this carefully about outlawing things, the world would probably be freer and less violent.